The history of Armstrong motorcycles is shown on a separate page. I acquired my Rotax 560E engined Armstrong MT500 motorcycle in 2017 in very poor condition after it had stood unused since 2006. Although the basic Armstrong MT500 motorcycle was developed for the British Army in 1984, this version was one of the very few subsequently sold for civilian use. Mine was bought new by Leeds Parks Department back in 1987. Also, unlike the kickstart Rotax 500 cc engined bikes sold to the army, my Armstrong is fitted with the larger 560 cc electric start engine – hence the reason it is referred to as an MT560. A picture of the original bike in Parks Service white in Leeds was sent to me by the person who used to run the team.

The condition I bought the MT560 in is shown below. The bike was largely complete with a few spares but it was in a very sorry state. The person I bought it from in Birmingham had tried to get the engine running but had eventually decided that it would be too complicated a project for him to carry out. It was advertised firstly amongst enthusiasts of this make of motorcycle and, when no interest was shown, was then advertised on eBay. Even then it failed to sell and I ended up making a low offer that the seller was happy to accept.

I already own an Armstrong MT500 and Harley Davison MT350, both of which were fully restored to original condition. However, since my Armstrong MT560E was a bespoke civilian version, I decided to make changes to it to make it a much better motorcycle. The main change was to replace the front end of the bike with that from an MT350 in order to benefit from a front disk brake. This involved replacing the forks, the front wheel, the speedo drive and the handlebar and controls to those from the MT350.

For this civilian version of the Armstrong, I decided to powder coat the frame in gloss black and to paint the rest of the bike in Deep Bronze Green (as used by the Army in the 1970’s) to retain a connection with the bike’s army heritage. Painting plastic components can sometimes be tricky but, as with my MT350 and MT500, the painted plastic on my MTs has managed to stand the test of time.

The steering head and swinging arm bearings and seals were all replaced. All the control cables and the speedometer cable were replaced by new items. The wiring harness was overhauled and repaired where necessary, and was also modified in order to work with the handlebar controls from a Harley MT350. The proper fuse box from an MT500 was installed on a bracket on the LHS just in front of the air box. The original battery tray was missing from the MT560 when I bought it and so I fitted one from an MT350 which took quite a bit of fettling to make work. A 14 AH gel battery was fitted although this was a very tight fit.

The front wheel was bought new but, since the rear wheel was in poor condition, I got the rim and hub powder coated in satin black and then rebuilt the wheel using stainless steel spokes. I also replaced all six bearings in the back wheel which is possibly one of the finest examples of over-engineering I have ever come across, save for the MT350 which has 7 bearings in the back wheel!

In order to mount the front disk brake from a Harley Davidson MT350, it was necessary to replace the left-hand Armstrong MT560 fork slider by that from an MT350. The original forks were overhauled. As is usually the case, the stanchions themselves were in very good condition and it was only the fork seals that needed to be replaced. The Ohlin rear shocks were completely rebuilt by a specialist and the springs given a new powder coating. A new front brake calliper was fitted as well as a replacement right-hand speedometer drive to mount on the wheel spindle.

The saga of my professional engine re-build is described below but, in the end, I had to remove the engine from the bike a total of four times which makes me a bit of an expert at being able to re-install it back into the frame. During the course of sorting out the engine problems, one of the original features I did not like was the primary filter. The one fitted to the MT500 is difficult enough to deal with but, because the MT560 has a starter motor like an MT350, the primary filter had to go somewhere else and that was behind the cylinder simply resting on top of the crankcase. In the picture above showing the bike after the original restoration but before the engine had to be re-built, the primary filter together with its rubber protection bands can be seen sitting on top of the crankcase just behind the cylinder. I thought long and hard about the need for the primary filter but, after the third engine re-build, I decided it was not necessary and have since left it off.

Having fallen backwards off my MT560 after catching my foot on a pannier rack, I always need to put the bike on its sidestand before getting off. However, the left-hand sidestand fitted to the MT560E (and later MT350E’s), which pivots on the swinging arm, is difficult to lower when sitting on the bike because the pannier gets in the way and there’s no projection fitted along its length to make this easier. My solution was to also fit the shorter right-hand sidestand found on most MT500’s that pivots just in front of the engine. My normal technique is, therefore, to put the bike on its left-hand sidestand to get on the bike and to put it on the right-hand sidestand to get off. If I was a lot younger, I might have got away with just one!

Engine Rebuild

Although I am an experienced motorcycle engine restorer, the Rotax 560E engine was in a very poor state and needed a lot of work doing to it including the fitting of a new piston and liner. I therefore decided to get it restored professionally by a firm that specialises in carrying out work on Rotax engines for Armstrong and Harley Davidson MT motorcycles. The firm had a very good reputation and I fully expected them to do a first class job and rebuild the engine to a high standard.

Rotax 560E engine after 1st rebuild

Unfortunately, this confidence turned out to be completely misplaced and the professional engine rebuild ended up being both expensive (£2,600) and a complete nightmare. When I installed the rebuilt engine in the restored bike and tested it, I found it clattered very loudly and obviously had a serious problem – for some reason, the engine restorer had failed to spot the problem when running the engine on his test rig showing how poor and ineffective his testing was! When I took the bike back to the company, the problem was diagnosed as a failing big end bearing despite the engine having just been rebuilt! The engine was therefore taken apart for the second time and the crankshaft assembly then sent away for the big-end bearing and conrod to be replaced. However, this work showed that there was nothing wrong with the old big-end bearing. It was only when the engine was being re-assembled that it became apparent that the problem was caused by both balance shaft bearings being loose in the crankcase – these had been rattling inside the engine. Surprisingly, I had to point out this obvious problem to the engine restorer who would otherwise have re-assembled the engine without doing anything about it again!

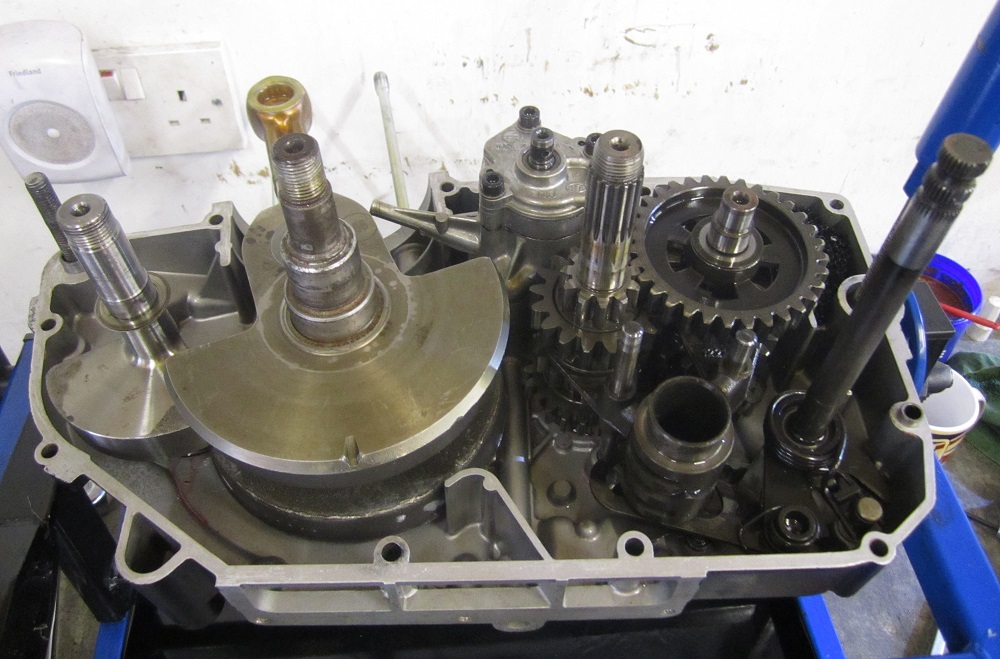

Rotax 560E engine during 2nd rebuild with brand new conrod assembly

Rotax 560E engine during 2nd rebuild with brand new conrod assembly

In response, the engine restorer tried to ‘glue’ the bearings back in place in the crankcase using a Loctite retaining compound but this proved to be unsuccessful as the re-installed engine clattered just as badly as before. When I took the engine apart for the third time myself, having lost all faith in the engine restorer by this stage, it confirmed both balance shaft bearings were still loose. If this was not bad enough, I then discovered other serious problems with the engine that had not been addressed during the two rebuilds. These included a badly damaged balance shaft, a worn out gearbox bearing, two worn out rockers, two worn out camshaft bearings and a badly worn rocker spindle mount. It was nothing short of shocking to discover the state of the engine following the two rebuilds especially as they had been carried out by a person I had previously regarded to be the UK expert on these Rotax engines.

It appeared as though the engine had been rebuilt the first time without any real effort made to identify and fix many of the fairly obvious problems it had. In particular, almost nothing had been done to the top end of the engine which remained largely in the worn out condition it was in when I purchased the bike. After the first rebuild, the engine looked almost as good as new but internally it was still in a very poor state. Why the engine restorer did such a slapdash job is still very difficult to understand, especially after two separate attempts at rebuilding the engine. However, having failed to carry out the work in a competent manner and having proven to be incapable of sorting out the problems, this so-called expert ended up paying a high price for the work after being forced in Court to provide a 50% refund (£1350) of the cost of the rebuild, most of which was the cost of new engine parts. He also had to pay the Court costs of about £300. This did not make up for all the grief I had been put through with this engine rebuild but at least the total cost for it had been significantly reduced and I also had the satisfaction of seeing the engine restorer fail miserably to offer any real defence in Court!

Fortunately, I was then able to rebuild the engine again myself and to sort out all the issues it had. At a further cost of about £400, the damaged balance shaft was replaced by a new one and the 6 roller or ball bearings that had not been replaced during the first rebuild, including the two failing camshaft bearings, were all replaced with new bearings. The balance shaft bearings were fixed in the crankcase using a much stronger retaining compound (Loctite 660 Quick Metal). The two worn out rockers were replaced by the rockers from my spare MT500 engine as was the gearbox main shaft with its worn out bearing. After three rebuilds, the engine now runs very well and is effectively as good as new.

This was the first time and probably the last time I will trust someone else to restore a motorcycle engine for me. The whole process cost me much more than I originally intended and also resulted in an enormous amount of extra work including the need for me to take the engine out of the bike and to then re-install it a total of four times. The engine restorer never seemed to grasp what was causing the clattering noise and appeared not to have the engineering nous to sort it out. I ended up taking him to Court simply to recover some of the costs since I knew I would have to fix the problems myself in the end. Surprisingly, I now regard myself as being very lucky to have had the clattering problem as, otherwise, I might never have realised how badly the rest of the engine had been rebuilt. Had I not found this out when I did, twelve months down the line, I might well have suffered a catastrophic engine failure.

Fourth Engine Rebuild

As described in my blog, after 1500 km, the original clattering noise started to return and required a further rebuild of the engine, including the replacement of the left-hand crankcase, to fully cure the problem with the loose balance shaft bearing. The engine now runs very quietly with no sound of the clattering noise that has plagued the engine since the original poorly carried out professional rebuild.

Fortunately, some two years after the original rebuild, I can now look at all this a bit more philosophically although my opinion of the engine restorer remains exactly the same; namely, a slapdash mechanic who appeared not to understand the fundamentals of motorcycle engine design! Despite the cost and enormous effort put in, I now have what is probably the best version produced of either the Armstrong MT500 or the Harley Davidson MT350, with the most powerful electric start engine ever fitted and with the best combination of brakes. After sorting out the engine issues, the bike is now in near perfect condition and an absolute joy to ride!

MT560E Performance

The original MT560E engine had a lower compression piston fitted but this was changed to a 10:5 high compression piston during the first rebuild which now gives the engine an output power of 55 bhp and a maximum torque of 55 Nm, compared with 28 bhp and 36 Nm for the MT500. The back wheel is also fitted with a 42T sprocket rather than the 47T sprocket fitted to the MT500 but the MT560E engine pulls the higher gearing easily.

The engine is fitted with a Dellorto PHF36 carburettor that I believe is original to the bike. On the road, the MT500 has enough power to cruise easily at 70 mph and to exceed 90 mph flat out and is enjoyable to ride. However, the MT560E is much more powerful and should easily exceed 100 mph flat out although this is something I have no intention of attempting any time soon. In contrast to my MT500 with a Mikuni carburettor giving a disappointing 42 mpg, the MT560E fitted with the Dellorto carburettor returns about 53 mpg giving it a much more respectable range of over 150 miles on a tank of fuel.

The MT560E has good road handling and more than adequate amounts of power and torque. With its well-padded seat, wide handlebars and comfortable riding position, it is basically a joy to ride. Also, with the adoption of the disk brake front end from an MT350E, the brakes on the MT560E are now perfectly adequate for road use. I enjoyed riding my MT500 but the MT560E takes that enjoyment to a different level.

In summary, my MT560E is a vast improvement on the Army’s MT500, with much better brakes and a much more powerful engine with electric start. The MT560E is a very rare bike being both a civilian model but is also fitted with a larger 560 cc Rotax engine. In fact, I have only heard of three other MT560E’s to-date with most of the other civilian models being 500 cc. If another MT560E came on to the market, I would definitely snap it up without a moment’s hesitation

MT560 Specifications

- Engine: Single cylinder, SOHC, 4-valve, 4-stroke

- Starting: Electric start and kickstart

- Capacity: 562 cc

- Bore/Stroke: 94 x 81 mm

- Compression Ratio: 10.5:1

- Max Power: 55 bhp

- Max Torque: 55 Nm

- Carburettor: Dellorto PHF36

- Cooling: Air cooled

- Lubrication: Dry sump

- Ignition: CDI with magnetic pick-up

- Transmission: 5 speed

- Final Drive: Chain

- Front Suspension: Marzocchi oil filled with 270 mm travel

- Rear Suspension: Ohlins nitrogen filled with 230 mm travel

- Front Brake: 230mm Grimeca hydraulic disc

- Rear Brake: 150 mm drum

- Rake/Trail: 25 deg and 92 mm

- Wheel Base: 1.4 m

- Seat Height: 855 mm

- Front Tyre: 90/90-21

- Rear Tyre: 4.00-18

- Ground Clearance: 220 mm

- Dry Weight: 161 kg

- Fuel Tank: 13 L

- Oil Tank: 3.2 L

MT500 Parts Suppliers

There are two very good suppliers of spare parts for both the Armstrong MT500 and the later Harley-Davison MT350: Force Motorcycles near Burton-on-Trent and LMS near Litchfield.

16,474 total views, 4 views today